At the east end of Llanychaiarn Church is a rank of five chest tombs, to members of the Hughes family of Aberllolwyn and of Morfa, in the Parish of Llanychaiarn, ( Morfa Bychan as we now know it) The five slate stabs adjoin one another like tabletops. Together they tell the story of a couple of generations. But the right hand slab is remarkable for a rare piece of naive artwork, the meaning of which intrigues me.

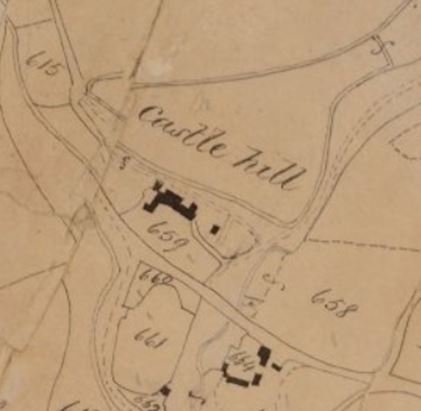

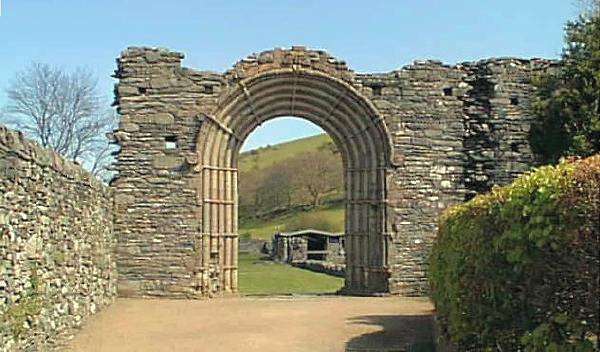

Graves of members of the Hughes family of Aberlllolwyn and Morva at the east end of Llanychaiarn Church

The slab reads ‘ Here lies the interred body of Anna Maria Hughes, second daughter of John and Elizabeth Hughes of Morfa, who departed this life the 24th of March 1777 in the 16th year of her life’. Her epitaph reads:

Adieu blest maid, Return again to Dust,

The’ Almighty bids to him submit we must

These little Rites a Stone, a Verse receive

Tis all a parent, all a friend can give.

Hers was the first of the five burials. Next to her are the graves of her mother Elizabeth Hughes, her father John Hughes of Morva, her sister Elinor ( 1764-1845) and her uncle Erasmus Hughes, her mother’s brother. It was Erasmus who occupied Aberllolwyn and died there, a bachelor aged 73 in 1803. As his epitaph points out he spent his life much preoccupied with the hereafter.

His life was spent in meditation on the Holy Scriptures and resigned in the hope of Resurrection to immortal Glory through the Merits of his Redeemer whoom( sic) he steadfastly trusted.

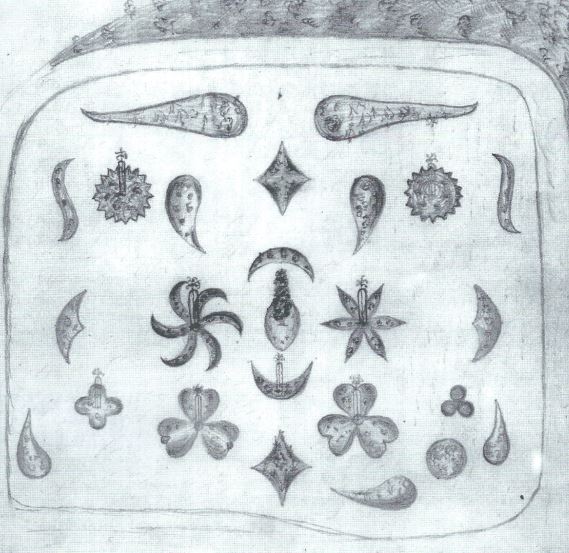

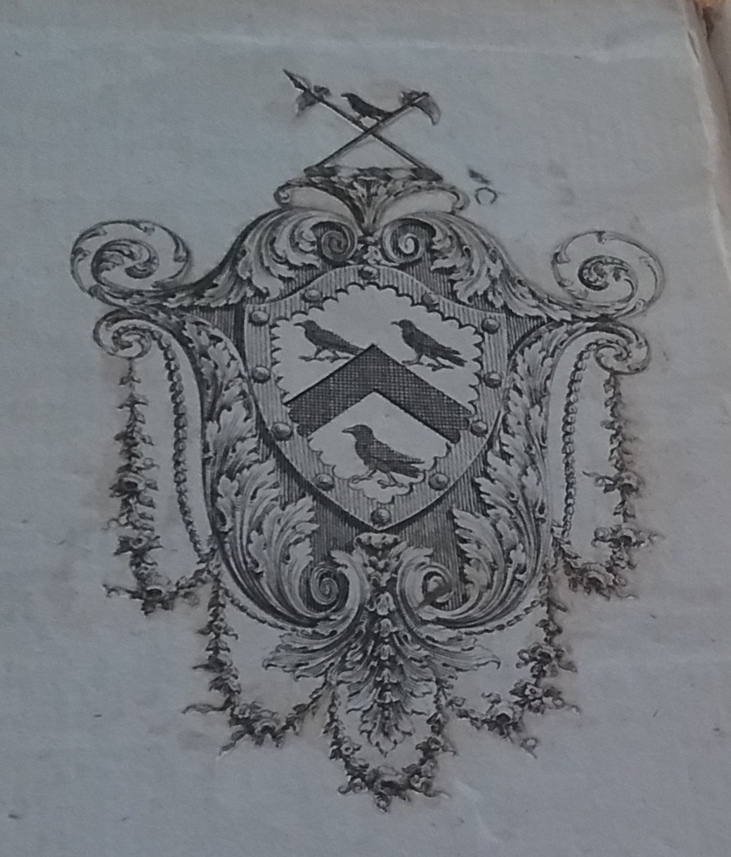

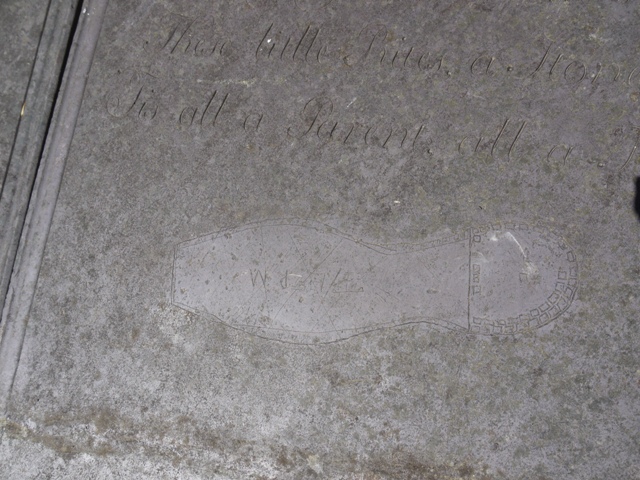

What is remarkable is that in addition to the copperplate verse engraved on Anna Maria’s slab is a remarkable bit of graffiti, the outline of not one, but two footprints, in neat square-toed shoes. The individual square headed nails securing the heel are each carefully inscribed. The positioning of the two footprints is informal, contrasting with the neat symmetry of the ornament and inscriptions. I don’t believe they were done in the mason’s yard.

Footprint on the grave of Anna Maria Hughes who died in 1777

A second and different footprint at the foot of the grave

Who carved them upon young Anna Maria’s grave? And why? or when?

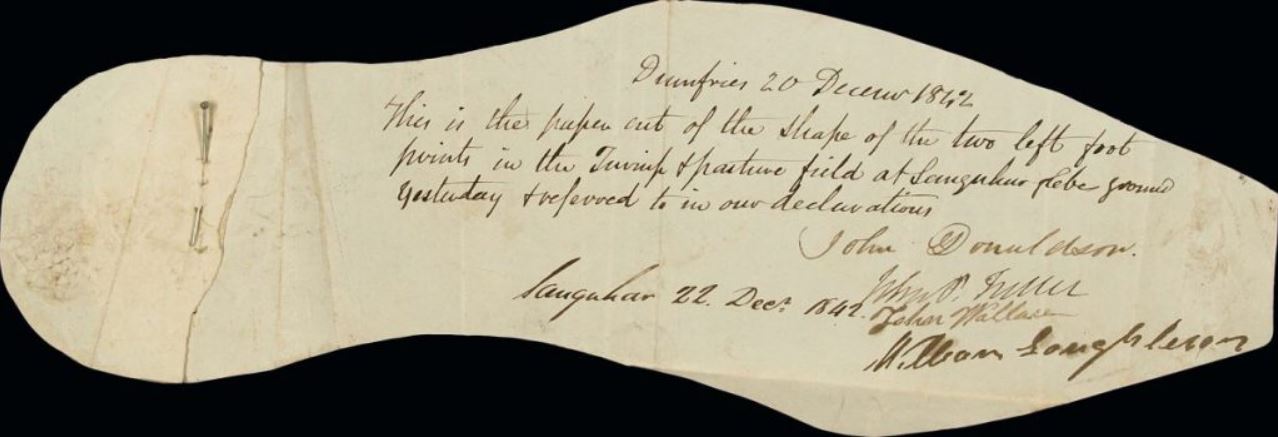

The other day I came across a very similar footprint, drawn on paper, in 1824. This was an example of a forensic drawing of footmarks at a crime scene:

A paper cut made in 1842 of left footprints in a turnip field at Sanquhar, Dumfries and Galloway

The shoe seems of a very similar style. What were shoes like in 1777? or was this carving added 50 years after her death?

I would love to hear of any other examples of footprint graffiti similar to this.

The full text of the other four graves is as follows:

1. Sacred to the Memory of Erasmus Hughes late of Aberllolwyn Esq., who died 13 March 1803 aged 73 years. His inscription reads: His life was spent in meditation on the Holy Scriptures and resigned in the hope of Resurrection to immortal Glory through the Merits of his Redeemer whoom( sic) he steadfastly trusted.

2. Sacred to the Memory of Elinor Hughes, daughter of John Hughes Esquire late of Morfa in the Parish of Llanychaiarn who departed this life 28th of January 1845 aged 81 years

3. Underneath lie the remains of John Hughes Esq late of Morfa second son of John Hughes Esq of Hendrevelen who exchanged this life for a Blessed Eternity the 27th day of October1806 in the 80th Year of his age. His epitaph reads:

Just upright merciful in all thy ways

In Christian meekness spending here thy days

Sweet sleep in Jesus thou dost now enjoy

Partaking happiness without alloy

4. Underneath lie the remains of Elizabeth second daughter of Thomas Hughes Esq late of Aberllolwne and wife of John Hughes Esq, of Morva both of this Parish who resigned her Soul to the Almighty giver the 12th day of November 1807 in the 71st year of her life. Her epitaph reads:

Adieu and long adieu thou ever dear

Thou best of Parents and thou Friend sincere

May thy survivors imitate thy worth

And live to God as thou didst while on earth

They are an evocative series of memorials: Erasmus Hughes was the only son of Thomas Hughes and Elizabeth Lloyd. One of his sisters Mary, married Edward Hughes of Dyffryn-gwyn, Merioneth and another, Elizabeth, married John Hughes of Morva. On Erasmus’ death the Aberllolwyn estate passed first to his sister Mary Hughes, and then to his niece Elizabeth Jane, another of John and Elizabeth Hughes’ daughters. It is noteworthy that all these Hugheses seem to have married men already bearing the name Hughes.