by The Curious Scribbler

It is difficult to engage with the mindset of the past, but my recent reading of The Otter’s Story by Dorothea Jones has given me a some fascinating insights on a now distasteful topic. It is otter hunting, a pursuit which was not fully abandoned in rural Cardiganshire until the mid 20th century. There are nice, cultured people alive today who will admit to having taken part in otter hunts in their youth. Otters heads – the mask – turn up mounted in country houses and salerooms and their paws still surface as Victorian jewellery. Not too long ago otter hunting was an accepted part of rural life and most people do not readily question what is normal in the society in which they grow up.

The Otter’s Story was published in 1880 by Dorothea Jones, sister of the Bishop of St David’s, and author of a campaigning tract dedicated to the reform of British workhouses. She was by then aged 52, an established author of articles in The Monthly packet of Evening Readings for Members of the English Church, and of two books. Her pen name was Gwynfryn. She is an adept writer, well able to conjure up the beauty of a day or the drama of a scene in prose. It is perhaps the more shocking then, that from such an unimpeachable middle-class Victorian should come such a piece of writing. Prose which is by turns cosy, lyrical, bloodthirsty and sexually charged.

If you want to understand what previous generations got out of pursuing a small cute fish-eating mustelid this is a remarkably good place to begin. It can be read online via Open Library http://openlibrary.org/ (search for The Otter’s Story, Jacobs Story), or on Nigel Callaghan’s estimable local site http://www.lloffion.org.uk/newdocs/the_otters_story/intro/display

She starts her account with several narratives about tame, pet otters. Just as Gavin Maxwell made clear in Ring of Bright Water 80 years later, they make engaging pets. The story potters along with captured otter cubs suckled by a domestic cat, otters reared with dogs, and grown otters catching fish for their masters. You are in little doubt, the author likes otters.

But the introductory pages have left a clue, like the pre-credit sequence to whet your appetite in the movies. The scene was opened upon a glorious early May morning on Cors Fochno ( Borth Bog) “with the hedgerows greening over and sparkling with dewdrops in the level sunshine”, the dark river “blue in the shadow, silver in the sun” flowing off the mountains. At the end of her anecdotes of captive otters, she rejoins this scene: to introduce the gathering of the hunt, the red and blue clad huntsmen some on horseback, the seething mass of excited hounds, and the hunt followers, “Welsh farmers in their old blue or grey coats, a rabble of wild hill boys awed by the novel sight of their betters” and two gaily clad village girls, one a smouldering Celtic beauty, the other, plain.

I won’t linger of on the details except to say that it is as sexist and gory as an episode of the popular historical fantasy drama Game of Thrones. There is agony, blood, demoniacal screams and lots of whipped dogs. “How could hunting be hunting without lashing of hounds and cries of pain from writhing creatures, round whom the sharp whipcord is cut with all the force of a thick lash and a strong man’s arm, roused to passion by excitement?” Men are men –standing tall and strong, violent, striding, shouting, digging out the otters holt to capture the cubs within. Women are egging them on – there is a moment when the she-otter and her cubs might have been spared and the hunt called off early. The master hesitates, and the pretty girl, like a spectator at a gladiatorial fight, seals the animals’ fate by her strident encouragement.

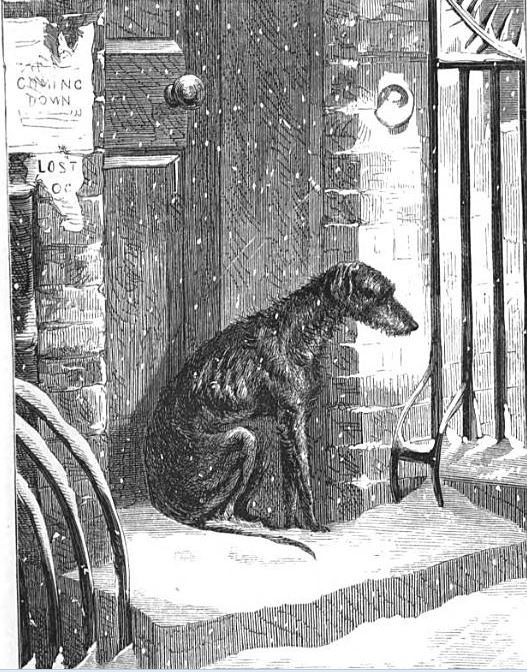

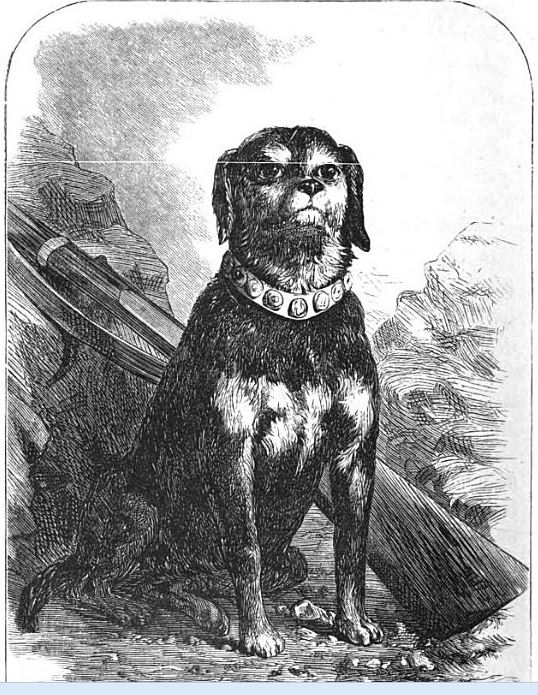

There is plenty of graphic death. In an early skirmish we meet the huntsman’s own terrier, Vermin, who “with his large soft eyes looking up through his long hair might have sat for the begging dog in Landseer’s portrait”. Vermin is unfortunately mistaken by the hounds for an otter, as he emerges from a hole in the bank into the water. He is torn to shreds before the men can rescue him, and his body is casually discarded. The dog otter is caught and killed, “screaming in an excruciating minor key”, soon afterwards.

The female otter escapes upstream with hounds in pursuit while some of the men set to work to dig out her young. One is mortally injured by the spade, two captured in a sack, one escapes to starve alone in the river. Gallant Mrs Otter comes back down stream where she is eventually speared on the two pronged pitchfork which otter hunters carry for this purpose. Even then in her desperation she twists and turns and prises her impaled body off the tines and drops back into the water, to be eventually grabbed by the hounds. It is an unsparing account of gore and death.

At the end of this celebratory tale the female otter hangs skinned from a tree and the master of the hunt bestows one of its severed pads upon the pretty Welsh girl. She colours prettily – “no charm, no jewelled gage-d’amour, could hold her with a sweeter spell than did just then that flabby, webbed, and mutilated foot”. But the man, on the point of making his move, has second thoughts. She is a bit too eager, “strangely hard…also she had been too conspicuous that day”, and he turns away. The final words of this psychodrama are four italic ones. “The otter was avenged”.

It would be nice to imagine that this was a pro-otter polemic – a wake-up call for people so unthinkingly cruel. But it was not written as such. The messages it carries are about the beauty and excitement of an otter hunt on a beautiful day and about the heady excitement of a testosterone-fired mob of men crazed by the hunt. There is only one lesson. The forward hussy does not get her man, and that is natural justice.