by The Curious Scribbler

For five months this blog has lain neglected, I last posted in January and now the longest day of the year is a whisker away. Spring has passed unremarked, though not unappreciated, and when I watched the family of goosanders on the River Ystwyth the other day they were no longer fluffy chicks, but handsome brown-headed fishing machines, indistinguishable from their mother, rummaging around underwater where the outgoing river flows fast over the stones at Tanyybwlch.

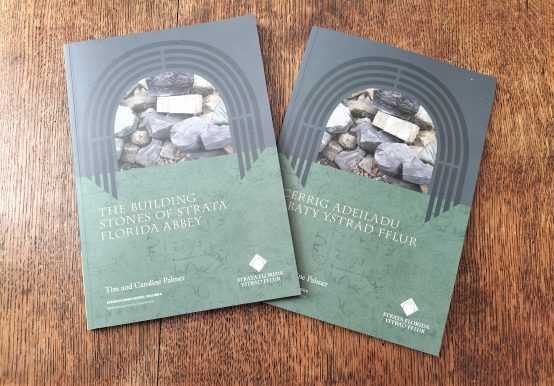

Many distractions have contributed to my silence online, one of which has been my collaboration with my husband on the production of a slim book Volume 6 in the Strata Florida book series. Yesterday it emerged emerged into our hands!

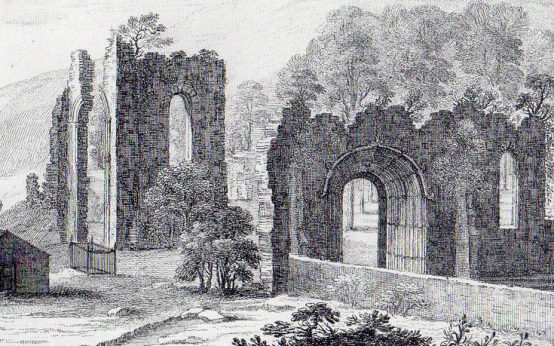

For the uninitiated, it must be conceded that Strata Florida abbey is not the most impressive of Britain’s ruined abbeys. When the Buck brothers traveled around Wales in the mid 17th century dedicating their engravings of houses, abbeys and castles to their gentry owners, a bit more of it was still standing and a gentlemans’ residence had been built on the site.

A detail of the Abbey ruins as shown in the Buck Print of 1741

Today only the west doorway still stands tall, largely thanks to restoration by the 19th century owner William Edward Powell of Nanteos. The tall fragment of the north transept visible in the picture fell during archaeological excavations in 1887, and much of the rubble excavated has remained in heaps and in sheds around the site. There are some choice pieces of sculptural stone in museums, at Arad Timescape in Rhayader, and at the National Museum of Wales.

Geological examination throws new light on Strata Florida, and this it the topic of our book. Many great stone medieval buildings were built out of materials quite local to their site, or at least they stood close to navigable rivers on which heavy materials could be transported. Strata Florida has none of these advantages. The locally available stone, Silurian greywacke, is suitable only for rubble-stone building, too hard to be accurately carved and inclined to fracture into layers. And Strata Florida is sixteen miles inland, uphill, and served by no navigable rivers. The gift of land by Lord Rhys of Deheubarth to the Cistercians in 1184 perhaps underestimated these disadvantages! Unlike Welsh vernacular buildings which were mainly of timber at the time, Cistercian abbeys had to be built to a plan, and freestone, reasonably soft and even-textured stone which could be accurately carved, was essential for the elaborate doorways, windows, vaulted ceilings, statuary and ornamentation. Specialist masons travelled the country working on prestige buildings such as this.

It turns out that several different types of freestone were used for building the abbey, and folk history still recalls that all this material came by sea and was laboriously carried inland from the coast at Aberarth. After the strenuous route up hill and across country the final obstacle was Tregaron bog where carts and beasts of burden could become mired. The exciting discovery is where the stone was brought from. Geology reveals that the carved freestone at Strata Florida came from Somerset, Gloucestershire, Anglesey, Pembrokeshire, Merioneth and probably Glamorganshire. Both sandstone and limestone are represented and fine details of texture, chemical composition, fossils and colouration enable the stones to be identified. It is apparent that stonemasons of ancient times knew a good deal about the properties of individual stone types. Some limestones decay faster in weather – and these sorts were used for internal decoration – others such as the medieval favourite, Dundry limestone from near Bristol, has remarkably resistance to weathering. The distinctive purple sandstone from the St David’s peninsula seems to have been used with other stone to create a polychromatic effect.

Three different kinds of freestone used at Strata Florida Abbey

With our book in hand the enthusiast can wander the site, finding the different stone types in the standing remains, in piles of dressed stone, and reused and incorporated into other buildings including Mynachlog Fawr and the parish church. Along with the other five volumes in the series it can be bought at Strata Florida or through the Strata Florida Trust website.