by The Curious Scribbler,

The leading exhibit in the Gregynog Gallery is undoubtedly the Canaletto, loaned out for the summer under an initiative to share the National Gallery’s collections with those of us in far flung corners of the UK.

The Stone Mason’s Yard by Canaletto

The Stonemason’s Yard was painted in about 1725 and donated to the National Gallery by Sir Thomas Beaumont a hundred years later. It depicts an early morning scene in a lesser square the Campo San Vidal. The rising sun casts long shadows across the scene and, as the accompanying caption describes, there is much human activity going on. There are gondolas and gondoliers on the Grand Canal, and women attending two lines of washing in the middle distance. The foreground shows women engaged in traditional activities – housework, spinning and childcare. At centre are the stone carving activities, a man with a mallet and chisel is carving a large block of limestone, while another with his back to us is splitting stone into pavier slabs. But the third stone mason on the right of the picture is the one who caught my attention, for here, working on the interior of a huge freshly carved basin or well head is undoubtedly a burly woman. It is unexpected to find a woman mason, but it appears that Canaletto painted what he saw. Surprisingly she is not mentioned in the caption.

The lady stonemason

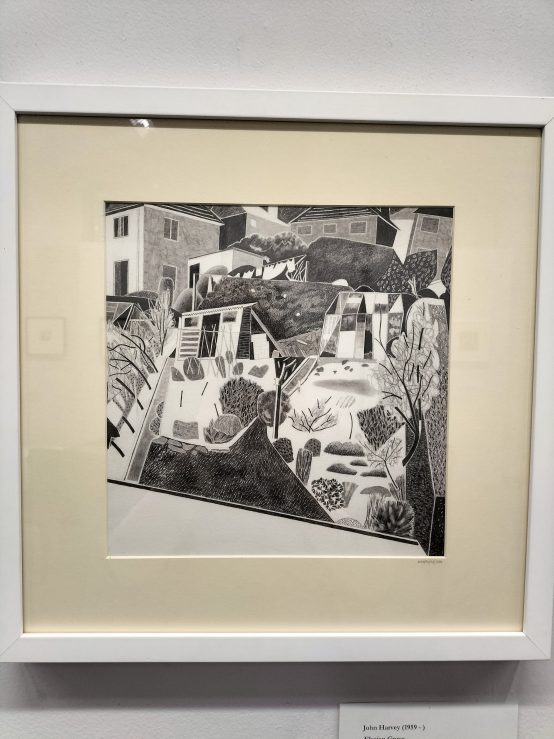

The rest of the exhibition is spread out to either side, Turn right for ‘Idyll’ scenes of rural Welsh landscape in paintings in the collections of the National Library, or turn left for ‘Industry’, – iron works, mines and quarries depicted over two centuries. Adjoining the industrial views are also a few abstracts, so abstract that only the initiated would know that they are about Wales. I’ve learnt a useful expression – ” deeply personal response” is a good description for baffling representations of named locations!

Among the more representational works, are pictures by Turner, Ibbotson, Richard Wilson, Thomas Jones of Pencerrig, David Cox and other well-known artists. For locals like me it was interesting to see a 1955 painting of Hafod by Joyce Fitzwilliams of Cilgwn, Newcastle Emlyn. The house is party roofless and viewed I think from the path up towards Pendre cottage. Demolition of the Italianate wing added by Henry de Hoghton has already begun.

Joyce Fitzwilliams’ Hafod 1955

Also of local interest was a painting by World War I Belgian refugee Valerius de Saedeleer of the land dipping down to the sea, probably near of Llanrhystud.

Valerius de Saedeleer Coastal landscape near Aberystwyth painted during WWI

Turning to the industrial side there are some powerful images such as Miners returning from Work by Archie Rhys Griffiths, a depression-era painting which nonetheless evokes the grandeur of toil. Many of the more recent industrial views are more grim or dismal in tone.

Archie Rhys Griffiths 1932 Miners returning from work

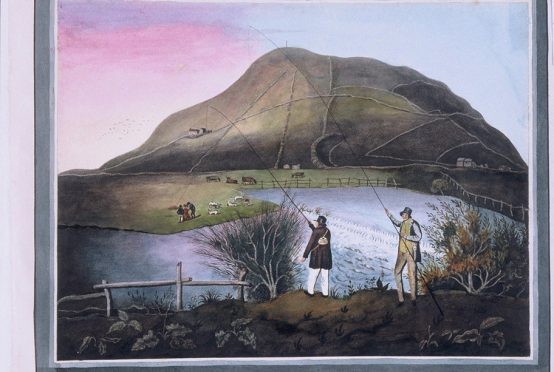

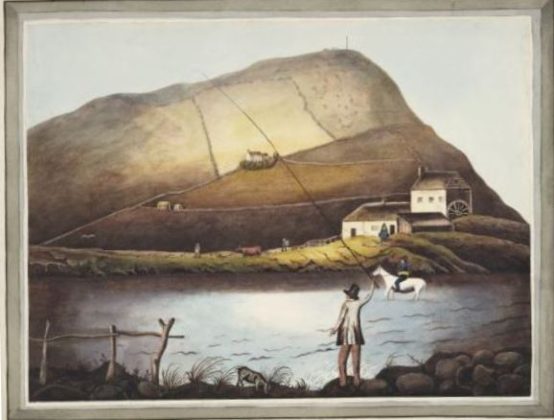

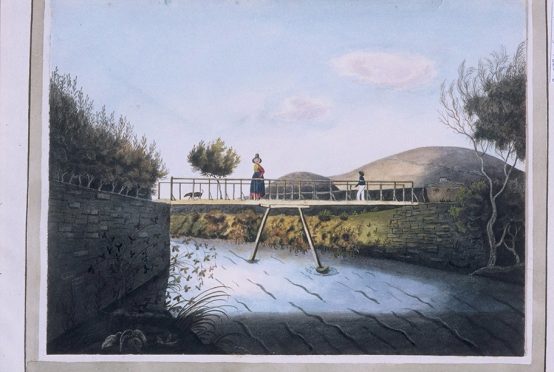

But my eye was caught by a work by Penry Williams, thought to depict the Dowlais Iron works. Like the Canaletto, the scene is bright and lucid, with long shadows cast across a foreground of great activity. The bare grassy uplands gleam in the background with neat fields and scattered farmhouses on the slopes, while lurking in full view is the industrial behemoth. Four tall chimneys, five flaming beacons, long sheds with with rows of chimneys each emitting a gleam of fire and puffs of white smoke. Everything is neat and new and sharply designed. The tall chimneys have ornamental tiers, and a huge sphere on a stone pedestal indicates an owner of wealth and discernment. Doubtless many men worked perspiring in the heat of these sheds, but the only humans we see are two top hatted gentlemen on horseback and a gardener with his wheelbarrow, meticulously edging a broad graveled path through the immaculate garden which adjoins the works.

Penry Williams’ evocation of industrial glory in the early 19th century

There came a time when industrialists moved away from their factories to unspoilt rural locations, sometimes donating their former parks to the people, but in the early 19th century one can sense the excitement of new industry bringing huge rewards to the iron masters, and new jobs to the rural poor. Penry Williams came from a modest family of stonemasons in Merthyr Tydfil. Without the patronage of the newly enriched iron masters he would never have studied at the Royal Academy or settled in Rome to pursue a career painting Italian scenes for young gentlemen on the Grand Tour.