by The Curious Scribbler

Nanteos Mansion, seat of the Powells

I’ve been re reading Juliette Woods article ” Nibbling Pilgrims and the Nanteos Cup: A Cardiganshire Legend” which was published in Nanteos – A Welsh house and its Families, Ed. Gerald Morgan (2001). In it the author carefully enumerates the written and the oral record to compare it with the fully fledged early 20th century legend of the Nanteos Cup. At its most florid, this damaged fragment of a wooden drinking vessel is believed to be the Holy Grail, brought to England by Joseph of Arimathea, cherished by the monks at Glastonbury, some of whom, at the dissolution of their monastery, fled with it to Strata Florida Abbey in Cardiganshire, from whence it passed into the hands of the Stedman Family of that community, and thus, by marriage to the Powells of Nanteos. In modern tradition the cup has spectacular healing powers, and its last custodian at Nanteos, Margaret Powell discretely massaged its reputation with testimonials from the healed. The cup is also sometimes alleged to be fashioned out of a fragment of the true cross – though this would not fit with the Holy Grail story in which Joseph of Arimathea caught Christ’s blood in the cup at the crucifixion.

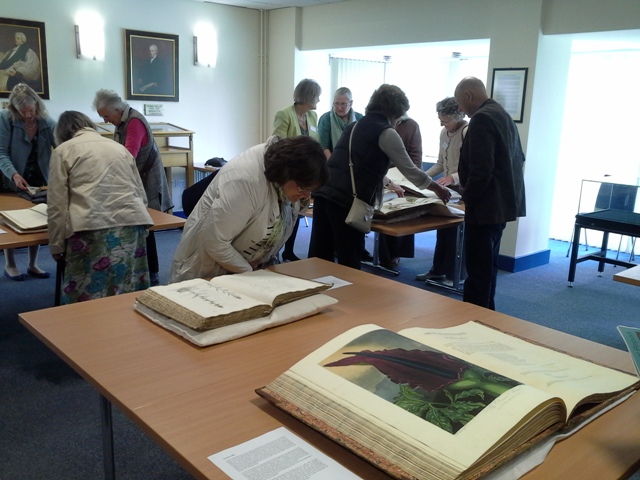

Juliette Woods gives a lot of attention to the common mechanisms by which such local legends are invented and augmented over time, but in essence her conclusions are that there is no written evidence of its importance and apparent healing powers until the mid 19th Century, and no indication of the Grail story until the early 20th. The cup first came under public scrutiny in 1878 when George Powell, a keen aesthete and antiquarian, allowed it to be exhibited to The Cambrian Archaeological Association at Lampeter. There was no allegation about the Holy Grail back then. It and another wooden vessel owned by Thomas Thomas of Lampeter were described as “supposed to possess curative powers”. The newly-fledged “Cambrians” as this genteel antiquarian society were generally known, were on a mission to ferret out antiquities from gentry homes and churches.

But the power of a good legend is in its ability to grow and mutate. Margaret Powell, who as a widow ruled Nanteos from 1930-1952 upheld the Grail myth, but with delicate discretion, refusing to allow the allegation to be associated with her name in print. Journalists, travel-guide authors and religiously-inclined scholars soon put in their pennyworth, and the Nanteos Cup gained followers. The Revd Lionel Smithett Lewis, Vicar of Glastonbury in 1938-1940 was one such enthusiast, fired up by A.E. Waite’s book Hidden Church of the Holy Grail (1909) which linked the grail to early Celtic Christianity. Smithett Lewis corresponded with Mrs Powell, and embellished the myth with the ‘discovery’ of a cupboard at Ozleworth Church, used by the Glastonbury monks to house the grail overnight when benighted too far from their abbey. Smithett Lewis wanted the Grail to be housed in a splendid reliquary at Glastonbury. Mrs Powell evidently did not co-operate and the correspondence ceased.

By the 1960’s the old mansion was in the hands of its first non-hereditary owner, Liverpool dealer Geoffrey Bliss, and the original cup had been transferred to a bank vault in the care of the Mrs Powell’s relative and inheritor, Mrs Mirylees. I visited Nanteos during the Bliss family occupancy, the house had been sold complete with most of its furnishings and portraits and despite the actual holes in the roof of one wing, it was open to the public as a stately home. And by then there was a facsimile holy grail to be seen in a lighted glass-fronted cabinet in the anteroom to the Library on the west end of the house. This may indeed have been the one said to have been made by a local craftsman to enable Mrs Powell to reduce wear upon the original unless its curative powers were actually required.

The ‘real’ cup meanwhile has gone from strength to strength. Throughout the 1990s you could send to America for a prayer cloth or tissue impregnated with water which has been poured from it. Presumably, as with homeopathy, this church in Seattle would allege that the greater the dilution, the more powerful the effect it would have. More recently, impregnated cloths were available from The Rt Reverend Bishop Sean Manchester, author of several non-fiction books, including “The Highgate Vampire”; “The Vampire Hunter’s Handbook”; “Mad, Bad and Dangerous to Know”; “From Satan To Christ”; and “The Grail Church.” However the supply dried up in 2014 when the cup was apparently stolen from the home of an elderly woman in Weston-under-Penyard, in Herefordshire.

Last year there was a further flurry of notoriety when the Grail had a spot on BBC’s Crimewatch. Muddying the history further, some news accounts showed an old photo of the missing object, ( though this was possibly a photo of Mrs Powell’s facsimile rather than the original) while others included illustrations from the Indiana Jones film starring Harrison Ford!

The Nanteos cup, or perhaps its 20th century facsimile featured in recent coverage of its loss

In June 2015 it was revealed that the cup had been returned but that no charges were being pressed. The police photo of the object they recovered closely resembles the 1888 sketch in Archaeologia Cambrensis and the early photos of the cup which are housed at the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historic Monuments of Wales rather than the picture above. I have recently heard that its new home is to be in the National Library of Wales.

The police photo of the recovered object looks more like the original Nanteos cup

Meanwhile new convolutions constantly develop. At Nanteos, which is now a smart country house hotel, there is a new garden feature in the old shrubbery adjoining the walled garden. A labyrinth by eco-mystic woodcraftman Bob Shaw leads on a contemplative circuit to a central sculpture which represents the Nanteos Cup, borne on a tapering plinth. The four sides of the plinth sides depict the mansion, Strata Florida, Glastonbury Tor and the Nanteos cup. Just to keep the legend alive.

The Sculpture by Ed Harrison at the centre of the new labyrinth at Nanteos

And Bob, who is a skilled craftsman working with traditional tools has also fashioned yet another Nanteos Cup, out of an ancient piece of timber he extracted from the Mawddach estuary. That will fox the carbon daters, as they strive to determine which cup is which! The wood could well be older than the true cross itself. Bob tells me that the hotel management are only too happy to keep his handiwork in their safe, and show it to favoured guests.

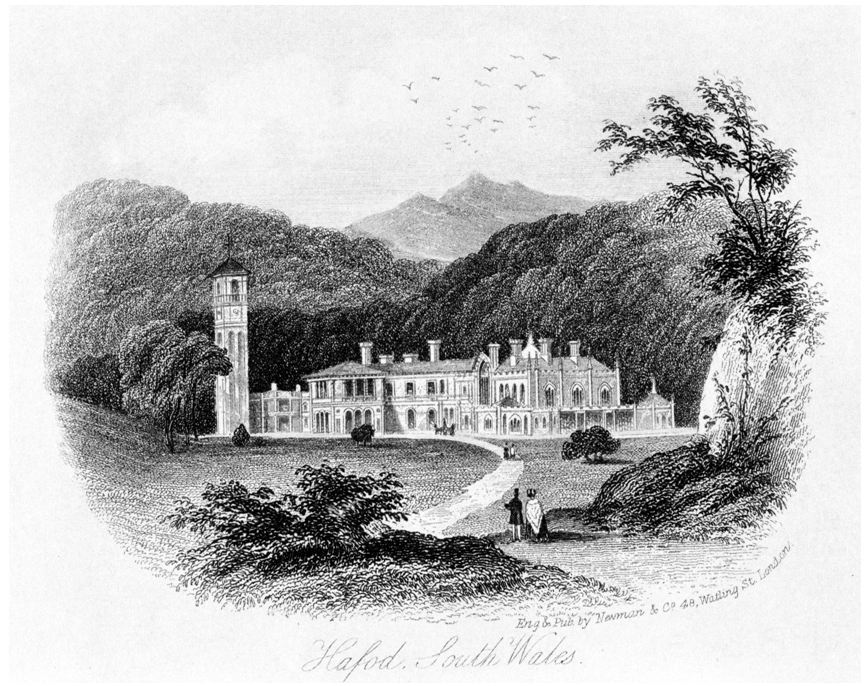

Then there is a further development, in the form of a historical novel, The Shadow of Nanteos, by Jane Blank published this year by Y Lolfa. Now I know this is fiction, but for many readers the distinction becomes blurred. Peacocks in Paradise, by Elisabeth Inglis Jones, which dramatises the life of Thomas Johnes of Hafod, is often perceived today as a purely biographical work. I found The Shadow of Nanteos unnerving myself because in it the very real Revd William Powell (1705-1780) who inherited on his brother Thomas’ death in 1752 is equipped with his historically correct wife, Elizabeth Owen. The book opens as he takes possession of Nanteos, his ancestral home. There however the resemblance ends: poor Elizabeth and William are supplied with quite different children, and a gothic storyline involving illegitimacy, adultery, leadmining, otter hunting, the death of their son, and finally the death of Elizabeth on the Nanteos kitchen table during a cesarean section to save the offspring of her steamy relationship with the bailiff. Ah me! What those Georgians got up to! But to return to the cup, – here all the components of the early 20th century fiction have been thoughtfully re-packaged to the mid 18th Century. Fictional Elizabeth invites round the local gentry wives and daughters, the Pryses of Gogerddan, the Lisburnes of Trawscoed and the Johnes of Hafod and they expound the whole story: Glastonbury, Joseph of Arimathea, Strata Florida, the Steadmans, the true cross, the Holy Grail and the nibbling pilgrims who bit pieces off the rim. ( The author must surely have read Juliet Wood’s painstaking work). Later in the book, driven to grief at the death of her eldest son, Elizabeth resorts to some very questionable frotteurism with the grail itself.

Nanteos seems a particular magnet for the wild assertion! There are already a number of popular but questionable ghost stories associated with it and suggestible readers of Jane Blank’s work may soon find themselves sensing Elizabeth Powell eviscerated on the kitchen table. And there is a steady increase in the historic characters which are claimed among its house guests. Local historians have long been enraged by the early 20th century myth, first promulgated in a tourist guide to Aberystwyth, that Wagner stayed at Nanteos and wrote Parsifal there. There is no closer connection than that the aesthetically inclined George Powell ( 1842-1882) was an admirer of his, and planned a journey to Munich with his friend Algernon Swinburne, the poet, to witness the Ring Cycle. Algernon Swinburne and George also shared an interest in flagellation and the works of the Marquis de Sade. But that connection scarcely justifies the current naming of one of Nanteos’ rooms as ‘The Marquis de Sade room’, nor the recent assertion that Robert Browning stayed there too!

The hotel website http://www.nanteos.com/news_detail.php?ID=51 reads as follows: Culture is all-pervasive at Nanteos Mansion with associations with leading European figures such as the composer Wagner and the poet Browning. It’s an easy concept to grasp, they are famous cultural figures and they both stayed at the Mansion while touring the country.

But they didn’t. Though hotel guests will enjoy believing that they did.

Like this:

Like Loading...