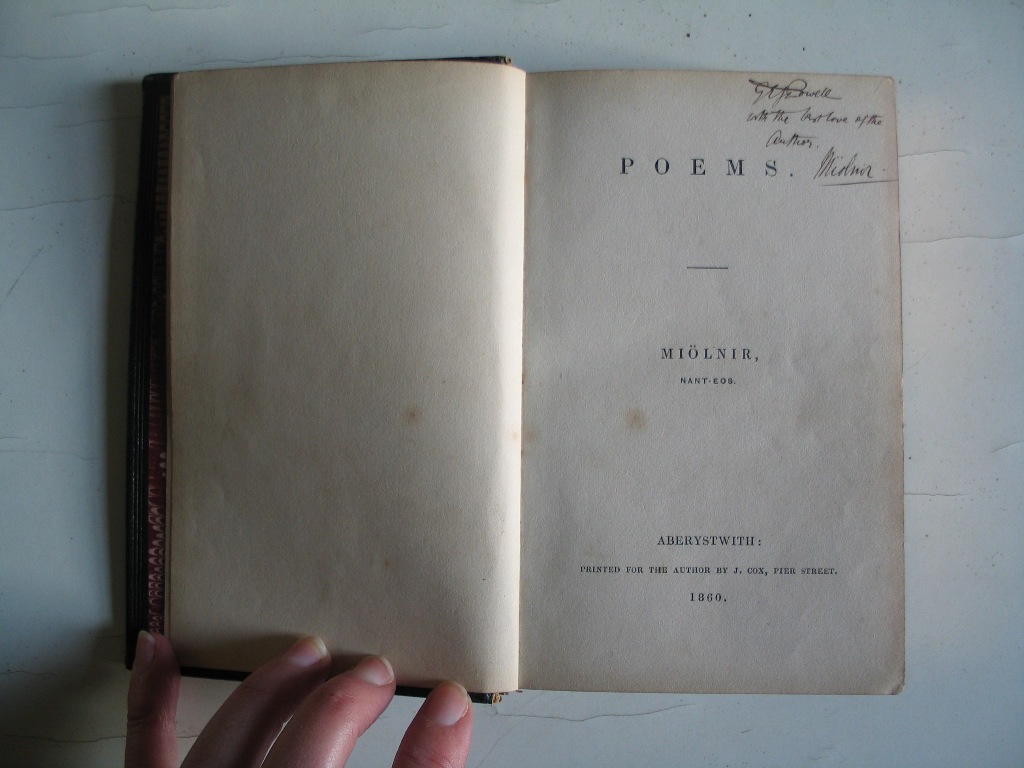

By the Curious Scribbler

I’ve been reading the work of a long-forgotten lady writer: Dorothea Jones of Gwynfryn.

I was led to her by the author Herbert M Vaughan of Llangoedmor, who, in his round-up of eccentric Welsh Gentlemen ( The South Wales Squires, published 1926) included a throwaway remark in his chapter on Literary Squires. “ At no great distance, on high ground that overlooks the great marsh of Borth, is Gwynfryn, the home and estate of Bishop Basil Jones of whose services to literature I have spoken elsewhere. The Bishop’s sister Miss Dora Jones was also a writer. There used to be a charming volume called Friends in Fur and Feather, which used to delight us in childhood with its accounts of the birds which haunted the swamps around Borth. But I have never come across this book it later life —- Ils vont sous la neige d’antan”.

Today there is nothing easier than finding long-forgotten volumes lost in the snows of yesteryear. In seconds, Google Books brought up the goods, an attractively bound volume in royal blue cloth ornamented with gold tooled leaves and flowers and red squirrels on its cover. I enjoy reading old books in the page view format, – except for the smell, everything of the material book can be enjoyed.

Published in 1869 it contains nine stories and a steel engraved illustration for each. Taken together they blend a delight in nature, pets, and the Welsh countryside along with a fervent approval for fox hunting and cubbing ( even if the victim has been a pet fox, being torn apart by hounds is represented as the most noble way to die).

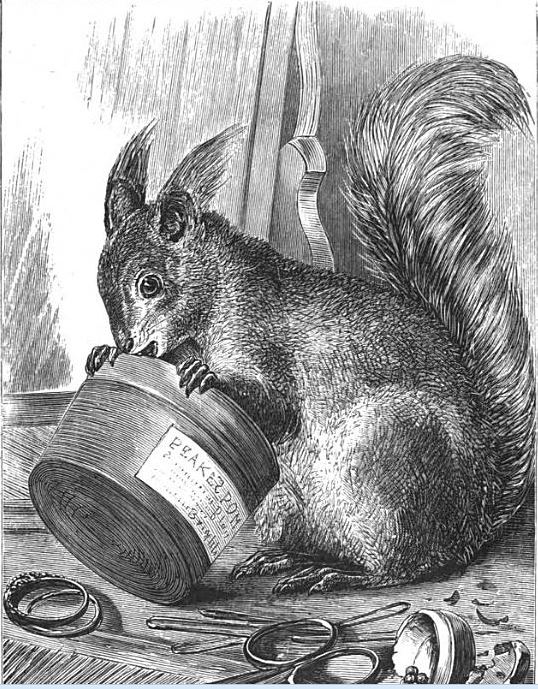

We know that red squirrels were formerly widespread in Ceredigion and in the first story a baby red squirrel is reared as a pet, takes up residence on the cornice in the drawing room, and eventually returns to the wild.

An illustration from ‘Friends in Fur and Feather’. The pet red squirrel helps himself to rhubarb tablets

In another two horrid boys have stolen two buzzard chicks from their nest on Borth bog and are feeding them on mashed potato. Our author rescues them and reared them on the abundant meat from fallen stock available to a gentry naturalist. “of suicidal mutton, drowned sheep, fished out of bog drains, they had plenty.” A quite gentle story about a young blackbird explains its Welsh name pig-felyn. Nothing to do with pigs, she tells her English readers, but the Welsh name for yellow beak. Unfortunately a cat gets the blackbird, much as last year a nestful of cute warbler chicks starring in Springwatch on the very same bog fell victim to a black cat.

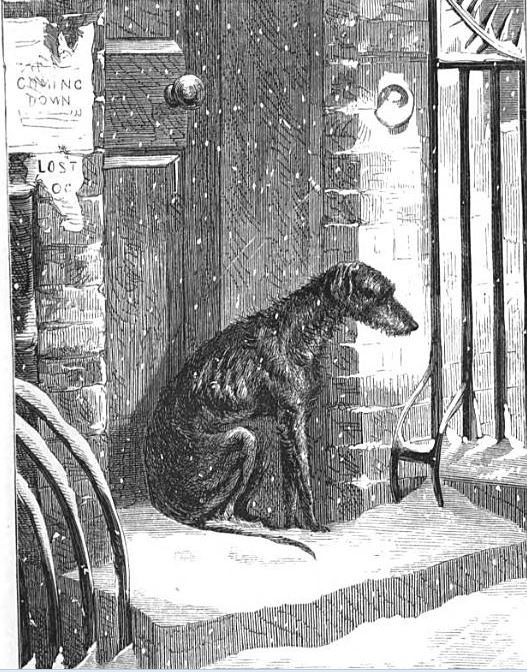

What is fascinatingly dated about the stories is their strong flavour that all is right with the world. In childhood her dog is bitten by an adder, becomes ill, and is later euthanized by one of the servants: “I was afraid to ask, for the sack and the bowstring had been familiar institutions amongst our pets of late”. In another story a donkey is tormented by three young gentlemen on horseback wielding their riding whips and chasing it across country. The fallen donkey’s injury is regretted, for it was a charming and reliable animal but somehow the young men, who do not provide their names, escape without undue censure. A story on the newly opened home for lost and starving dogs in London (the early RSPCA) remarks cheerfully that unattractive stray dogs unlikely to be re-homed will be happier to have their lives terminated “ then they have to take prussic acid and their poor little troubles are over. ”

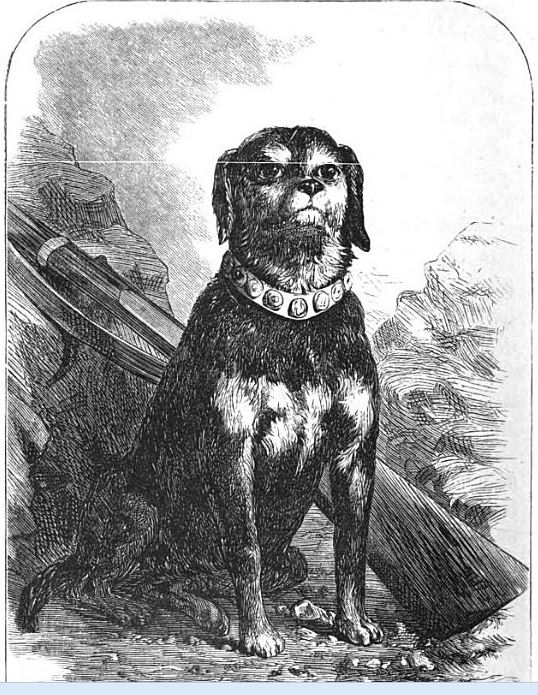

Another dog story glorifies the military campaign of Bob, a middle sized mongrel, with Her Majesty’s Scots Fusilier Guards in the Crimean war. Having escaped all injury during the two year campaign he was knocked down in the London streets when marching with his regiment, and subsequently stuffed and displayed in the United Services Museum at Whitehall.

‘Bob’ of Her Majesty’s Scots Fusilier Guards. ( a likeness taken after he was stuffed)

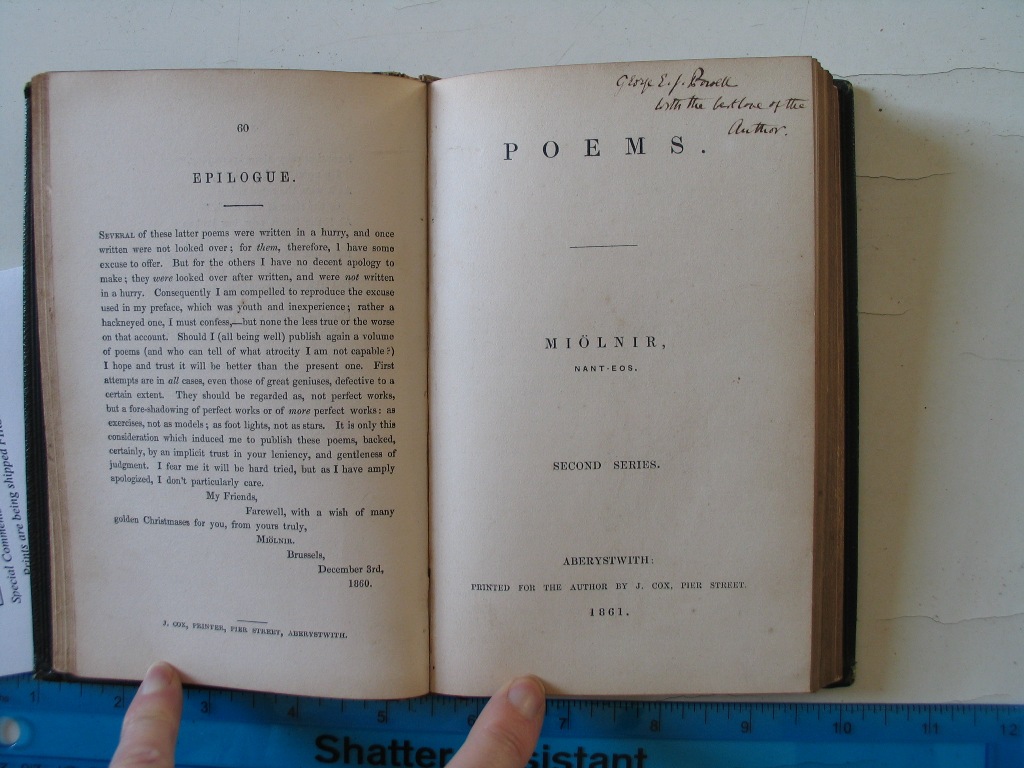

An illustration from ‘Friends in Fur and Feather’.

Friends in Fur and Feather was clearly a bracing if sentimental read for Victorian children like Herbert Vaughan and in 1883 a slimmer and un-illustrated edition of eight of the stories was published by George Bell and Son of London in the Bell’s Reading Book Series for schools.

The true identity of the author, ‘Gwynfryn’ is in danger of being lost to sight.

The copy I had read on Google Books was stamped ‘Bodleian libraries’, so I sought it through the Bodleian electronic catalogue. My indignation was aroused to find that the book has been attributed to the output of an American nature writer, Olive Thorne Miller, (1831-1918) who included amongst her output a book called ‘Little Folks in Feather and Fur and Others in Neither’ which was published in 1880. Miller, though, was an urban New Yorker, not a Welsh woman and could not have written these stories.

I am in correspondence with the Bodleian to reclaim Gwynfryn for Wales!

Dorothea Jones can, with a little effort still be traced. She was born one of twin girls on 18 March 1828 at Gwynfryn to William Tilsley Jones and his wife Christiana. Already in the household was an older brother, William Basil Tickell Jones who was later to become Bishop of St Davids. He was the only child of an earlier marriage to Jane Tickell of Cheltenham. In the following ten years six further children were born to Christiana but it must have been a harrowing time: between 1835 and 1838 five children died, including Dorothea’s twin Christiana, and her nearest sister Josephine. Perhaps such a childhood fosters a robust attitude to death.

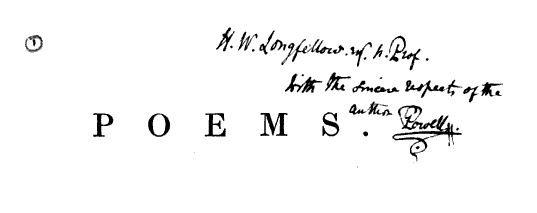

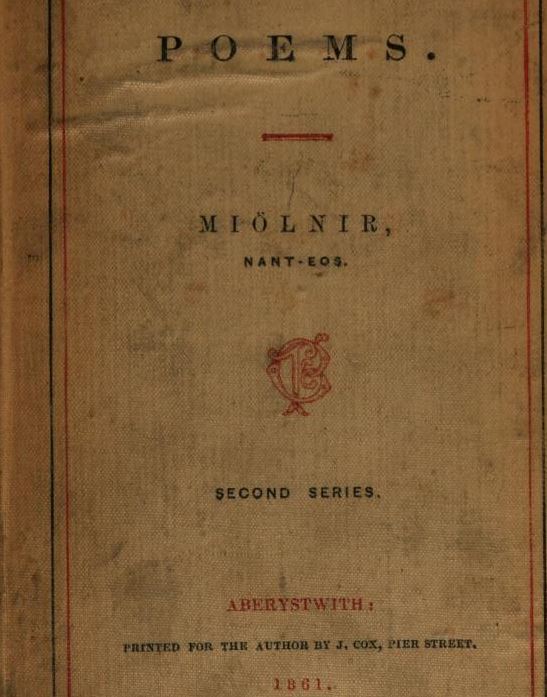

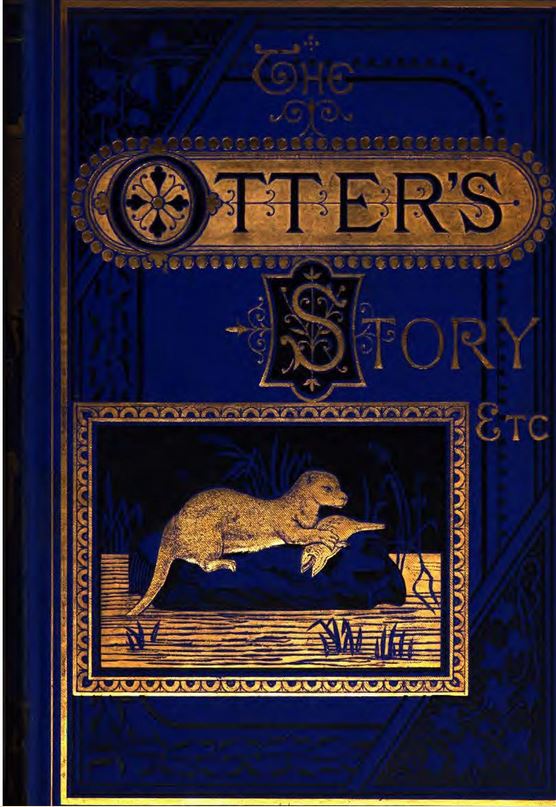

Dorothea Jones is one of the few women to have been awarded her own entry in the Dictionary of Eminent Welshmen by T.R. Roberts published in 1908. In it there is a reference to another of her books, which is described due to a misprint as “The Other’s Story”. It took a bit more searching to find this, but the result was gratifying, as I at last came across “The Otter’s story” by ‘The Author of ‘Friends in Fur and Feather’, ‘Sick and in Prison’ Etc., Etc.’. It was published in 1880 in London, also with a pretty blue and gold tooled cover, and is dedicated in print ‘Affectionately and gratefully inscribed by the writer to her brother William Basil, Bishop of St David’s’. This too is in the Bodleian and attributed to Olive Thorne Miller!

The cover of The Otter’s Story Etc, by the Author of ‘Friends in Fur and Feather’

Published in London in 1880

The National Library of Wales also has a number of copies of Friends in Fur and Feather, but simply catalogues them under the pen name of Gwynfryn.

There are other traces of lost history to be gleaned from these old story books; the identity of their first owners. A nice 1869 copy in the National Library of Wales is inscribed as a gift to Louisa Frances Best on December 7th 1869 and was given with Arvie’s Best Love. A reading-book version from 1883 was the property of Florence Richards, while another 1869 copy in the New York Public Library was given to Jennie Ryder, Xmas Gift from the SS of the Chapel of St Christopher, Thomas Sill, New York, to mark the Feast of the Holy Innocents in 1870.

As family history enthusiasts search the past for their relatives on the web, it is not impossible that Louisa, Florence and Jennie may one day be spotted by their kin, led to this website by the re-publication of their names.