Tanybwlch beach is one of those beaches which grades its pebbles. It forms a generous arc south of the concrete jetty which shelters the harbour at the mouth of the Ystwyth and Rheidol rivers. At the north end the foreshore is an ankle-breaking slope of big round stones up to the dimensions of a small loaf, and even near low tide mark there are pebbles, not sand. At the middle of the curve, by contrast, is a beach of dark sand, winnowed by the steep suck of the waves. Down near the southern end, below craggy Alltwen the sea only deposits a floating load. Here one finds lobster pots, fishing floats, the occasional dead dolphin, and great quantities of driftwood and uprooted seaweed. Of sand and pebbles there is very little, they move inexorably northward, leaving the rock pools largely free of sediment.

This is my favourite beach. Not for swimming, the shore shelves steeply and the undertow is well known, but for its elemental wildness, its dark grey pebbles, and gritty sand jewelled on close inspection by many shades of tiny smooth pebbles, amber and creamy quartz, jasper, granite, mica, all alien travellers brought by the glaciers which carved their way across this land. Niall Griffiths in his debut Aberystwyth novel Grits was so taken by Tanybwlch beach’s dark brooding grandeur that he described it as a volcanic landscape. But it is not. Its jagged outcrops are of the prosaically named Aberystwyth Grits – greywackes to the geologist, layers of muddy silt hardened to stone since their accumulation under Silurian seas.

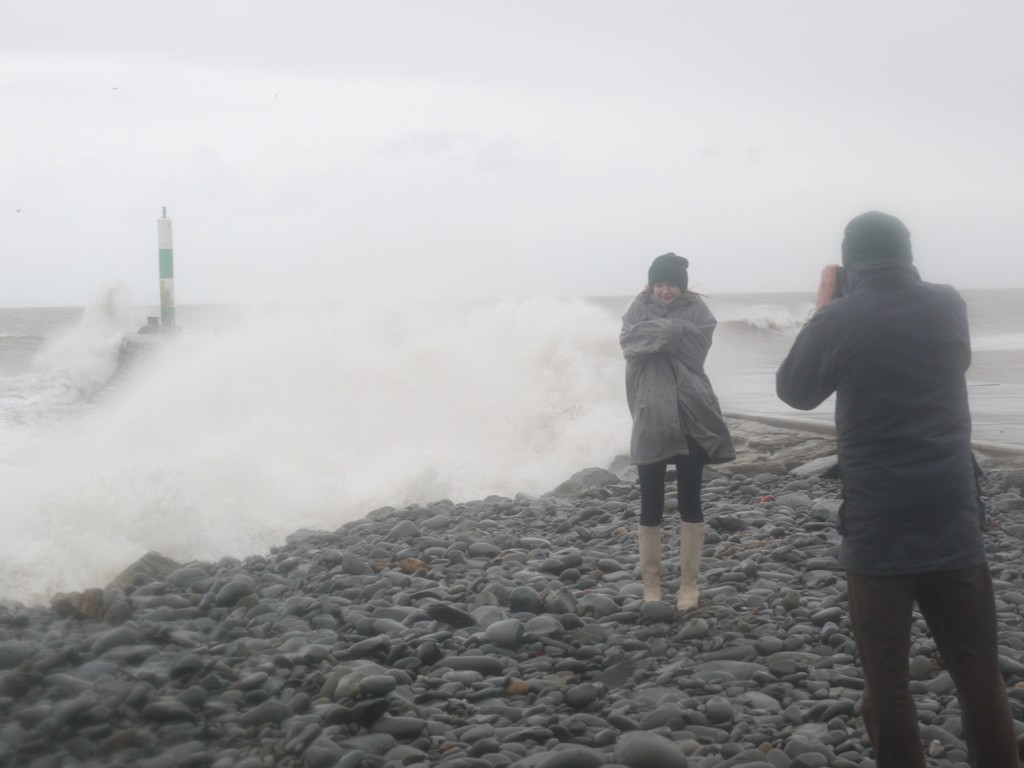

The wild grandeur of Tanybwlch beach

Along the shingle bar which separates the beach from the low lying meadows beside the Ystwyth runs a rough road. In Victorian times a small railway ran along it bearing stones from the quarry at Alltwen to their destination in the buildings of the town. In the twentieth century it gave access to the length of this deserted beach, a refuge for rod fishermen encamped along the shore, wild campers, insalubrious assignations, and the occasional impromptu party fuelled by the copious driftwood. In summer brash tattooed men from the Midlands would roll up, with trailers, power boats or jetskis and launch them from the sandy middle of the bay. That pastime ceased though, when the northern half of the beach was designated a local nature reserve, and a new barrier prevented vehicular access along the bar. On balance it was a good decision, but not everyone was instantly won over and several years of barrier vandalism followed the change. In recent years only keyholders such as the adjoining farmer have driven along the bar, and the life of the beach has become pedestrian, though not necessarily sedate.

The recent storms have wrought an elegant transformation. Approach the car park at the end of Penyranchor and you will find it closed, for it is impassible due to a liberal scattering of those big round beach stones. Press on beyond the barrier and there is no road to walk along. Huge wave force has lifted the sloping pebble beach up over its former crest and deposited it on and beyond the road. Waves surged over the beach barrier throughout its length, taking a slew of stones down the landward side, running briskly through the old shingle where the ancient prostrate dwarf blackthorn grows, the seawater rejoining the tidal Ystwyth river beyond. And the consequence is the most elegant re formation. A sculpted bank of round beach stones rises from the beach and descends, less steeply to the grassy slope descending to the river. Harder walking. Quite undrivable. But no one needs to drive through a local nature reserve anyway.

The new beach profile has entirely buried the road along the strand.

Farther to the south the encroachment has been of clean gritty beach sand. Here the sea has tended to break through in the past and the road runs on a barrage of concrete, with low walls on either side, a nice spot to sit and look out to the westering sun, or east to the sharp bend which the Ystwyth takes as it meets the strand. It’s still a nice place to sit, but its road function now looks remote. Erosive forces have cleaned away the ground where the concrete ends. It is now a massive step up onto the concrete road at either end.

The concrete road at the centre of the bay has been excavated at either end by the waves.

As I’ve said, the sea at Tanybwlch removes stuff at the south end of the arc, and moves it, the heavier the further, to the north. So as one approaches Alltwen there is less sand or pebbles scattered on the foreshore. Instead the sea has torn away at the turf and the big quarried blocks placed there as sea defences. Some of these big stones from Hendre quarry have actually been trundled up slope and over onto the former road.

Tanybwlch Beach. Turf and sea defence stones rolled back by the force of the sea

It is here, near the south end that the beach last breached, in a big storm of 1964. It hasn’t happened yet, but there are no national plans to defend this piece of seashore, and it doubtless will. The consequence will be most picturesque. With this (and during many lesser storms) the fields below Plas Tanybwlch become a shallow brackish lake, visited by appreciative gulls and waders. The strangely rounded hill fort of Pendinas looks well with the blue winter sky reflected at its foot. The dark bulk of Alltwen also rears elegantly above the foaming rollers to the one side and a still wide pool on the other.

The tranquil winter sunshine falls on a large salty flood below Plas Tanybwlch

Pendinas stands above the new brackish lake on the Tanybwlch flats

Like this:

Like Loading...